Born in Ohio and now based in Boston, Massachusetts after a near-decade in New York, Caleb Halter is, like many designers, someone whose creativity isn’t just manifested visually.

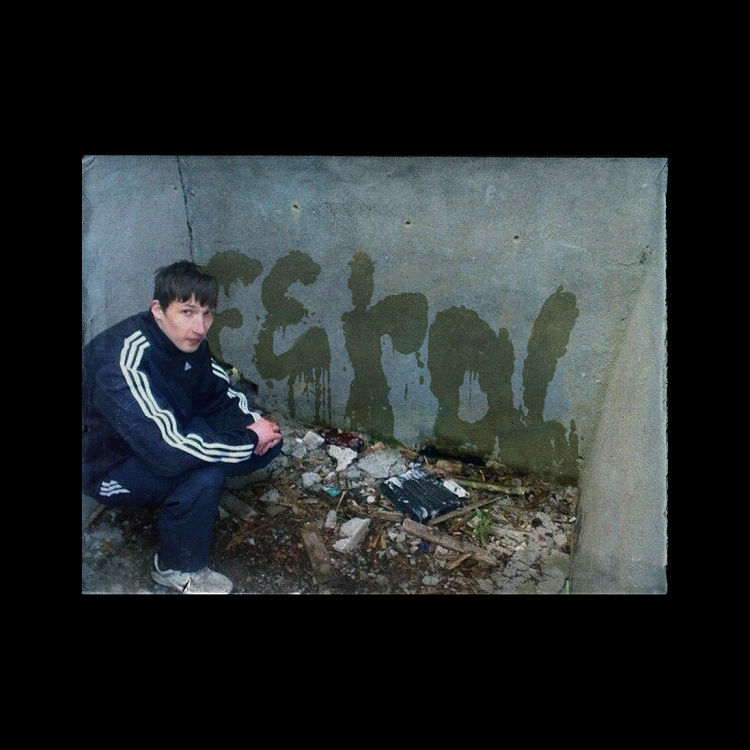

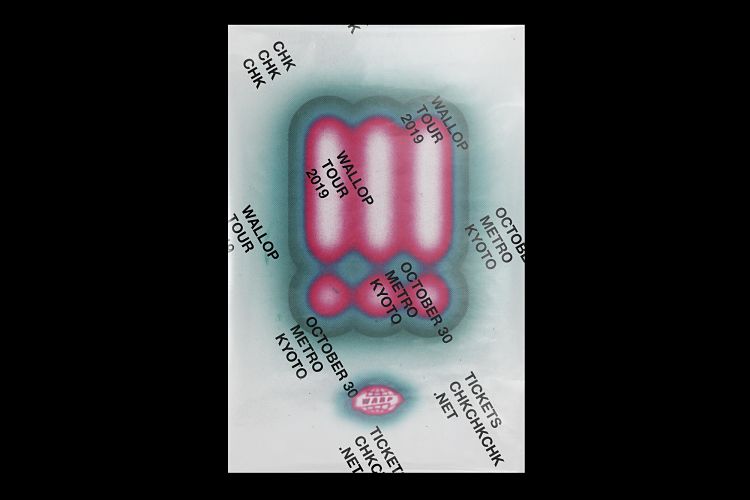

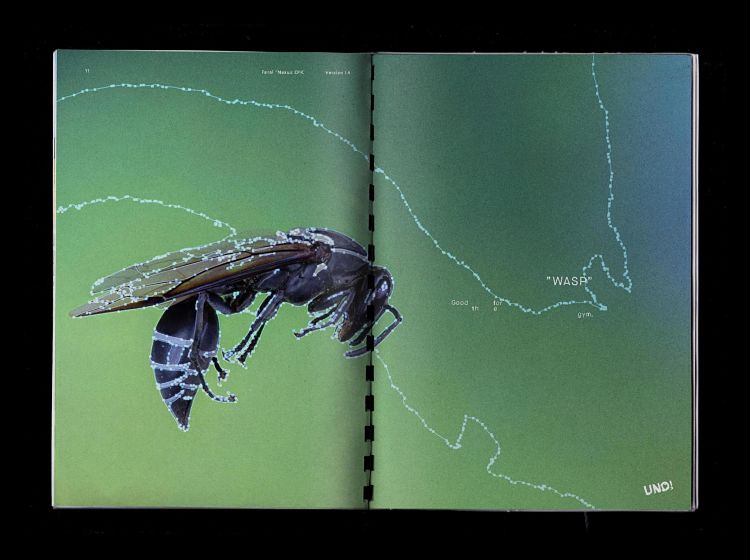

Since around 2018, he’s been making music under the alias Feral. “Caleb means dog, so it’s something along those lines,” Halter explains of the name. “Thematically it’s a good reminder to not be afraid of letting a song go wherever it wants to without reigning it in.”

While Feral’s music has appeared in compilations from record labels including Gilles Peterson’s Brownswood Electric, Ghostly, LuckyMe and Bromance Records. “Originally making music served as an outlet from design, so I made a conscious effort to keep both practices apart just to protect making music almost a form of therapy,” says Halter, “but over time I’ve come to appreciate how the tension between them can help make the work better on both fronts.”

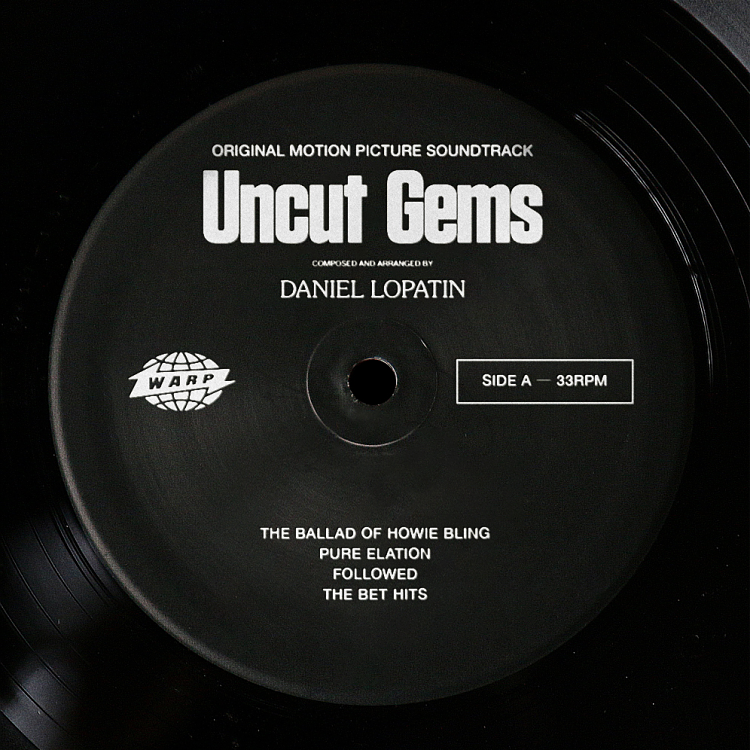

It makes sense to finally unite the two sides of his practice: his design studio RegretsOnly, which was formed last summer, works on brand identities and graphics for music clients including Warp Records’ Daniel Lopatin (also known as Oneohtrix Point Never), !!! and Battles, as well as the likes of the New York Times to 21st Century Fox.

It makes sense to finally unite the two sides of his practice: his design studio RegretsOnly, which was formed last summer, works on brand identities and graphics for music clients including Warp Records’ Daniel Lopatin (also known as Oneohtrix Point Never), !!! and Battles, as well as the likes of the New York Times to 21st Century Fox.

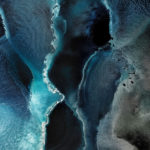

The result of his more recent intermingling of his design and music work is a record titled The End, with its first single, In Flames, released last month. Halter has created all the artwork and moving image pieces, working with photographer Tim Saccenti to create the album cover.

Halter is mostly self-taught when it comes to design, having began his professional career designing tour graphics (mainly for country musicians) aged 19. He went on to work at studios such as Gretel in New York, where he says he “really learned how to formulate a real thought,” rather than just being able to use design and software tools. “Their process is so rigorous and so thorough, it completely opened my eyes to seeing design not as an aesthetic choice but as a way to create clarity,” he says. “Because I never went to design school I saw my time there as a sort of master’s program in branding.” We had a chat with him ahead of the album release about the links between sound and visuals, his music-making tools, the “painful experience” of being your own client and more.

Halter is mostly self-taught when it comes to design, having began his professional career designing tour graphics (mainly for country musicians) aged 19. He went on to work at studios such as Gretel in New York, where he says he “really learned how to formulate a real thought,” rather than just being able to use design and software tools. “Their process is so rigorous and so thorough, it completely opened my eyes to seeing design not as an aesthetic choice but as a way to create clarity,” he says. “Because I never went to design school I saw my time there as a sort of master’s program in branding.” We had a chat with him ahead of the album release about the links between sound and visuals, his music-making tools, the “painful experience” of being your own client and more.

Why did it feel like the right time to finally unite your music and design practices?

Why did it feel like the right time to finally unite your music and design practices?

It wasn’t so much of a choice as an inevitability, I think. Funnily, making music started as an outlet from design—when you love what you do, projects can have a tendency to creep into every moment of your day and I think it’s useful to find something that forces you to let the paint dry a little bit.

I initially made a conscious effort to keep music and design apart just because I wanted to protect making music almost a form of therapy, but I think I’ve grown to a point in both practices that I can use the tension between them to make the work better on both fronts. More practically, after signing with a label, it simply needed artwork!

What sort of tools do you use to make your music?

What sort of tools do you use to make your music?

Disappointingly, everything is finished end to end in Ableton. I wish I had a hardware setup worth speaking about, but because the time I spend making music is always precious (and in short supply) I use whatever means have the least friction, which essentially is just a laptop with lots of plugins.

The challenge has been how to get something that feels tactile and human out of such a sterile setup. A lot of what I do initially is create something that feels really pristine and expensive sounding, and then flatten all the layers, swap things out and patch them back together, almost like a remix of myself, until eventually that original pass is just the thread holding an amalgamation of all these tiny pieces together.

It’s really about getting completely out of the way and letting an idea pass through me, and not letting my own notion of what it should be or who it should be for skew what it becomes along the way.

What’s your background in terms of music making?

What’s your background in terms of music making?

I have a background in classical cello, bass, and drums, but I would have to credit the start of both design and music to pirated software at age 12. If this is any indication of my personality, my starting place wasn’t making something new as much as removing things I didn’t like—a musical bridge that felt extraneous, or a snare that didn’t gel (at least to me), and going from there—edits to remixes, to pulling the samples out altogether and filling them with something new entirely.

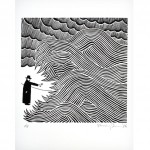

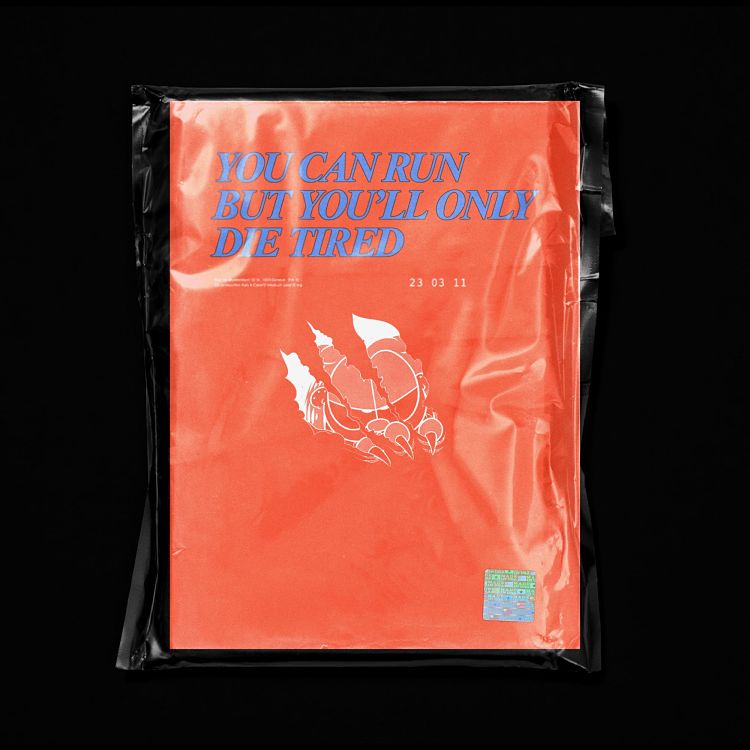

What was the thinking behind the single design? Who’s the wee character? How did you make it?

What was the thinking behind the single design? Who’s the wee character? How did you make it?

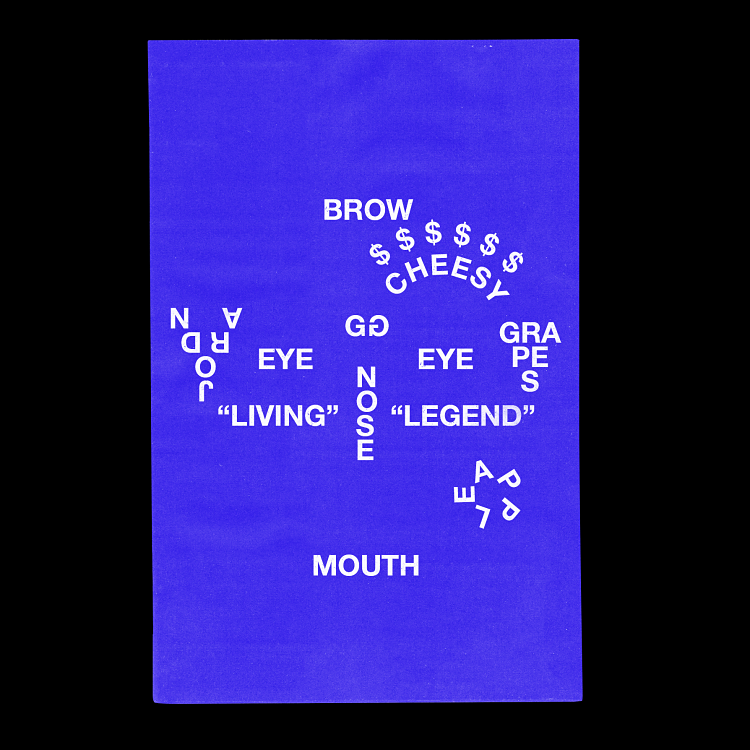

The whole record is sort of an exploration of this idea of substance without pretense. I can’t be the only person who likes Basinski and Skrillex, Soufflé and Funfetti. Because the record is on the more challenging/experimental side, I wanted the art to feel more familiar.

So the design started with looking back at the visual vernacular of my childhood in Ohio—firework packaging, Calvin Peeing, Frisch’s Big Boy, etc. and creating something that felt a part of that world. The process was really just pulling lots of references, sketching him out and roughing him up a bit.

How do you find it setting yourself a design brief, and sort of being your own client?

How do you find it setting yourself a design brief, and sort of being your own client?

Having yourself as a client is a really interesting, painful experience. It forced me to start to figure out what my visual style is without anything else to really lean on or jump-start the conversation. I think it’s way more challenging to stare at a blank canvas and create something than to be handed a brief, but it’s been fun to explore and has definitely informed the way I work with clients to better articulate and express ideas of their own, it’s not easy.

What advice would you give to young designers and grads who are looking to set up on their own?

What advice would you give to young designers and grads who are looking to set up on their own?

I think I’m probably too early in the founding stage of the studio to offer any meaningful advice to business-building, but on a personal level my advice would be not to let anyone set a pace for you.

It’s important to have goals, and the respect of your peers and mentors, but titles are a construct within a studio that have no real meaning out in the world. Validation has to come from inside. You are the star of your own movie, but you’re just an extra in everyone else’s, so free yourself from getting wrapped up looking for their approval.

You might like...

- Autobahn - November 26, 2021

- Alphabetical - November 12, 2021

- SOFA Universe - November 8, 2021